Penn Museum of Art and Archaeology Volunteer David Biberman

Remembering Bob Dyson

By Colleagues and Former Students

The Penn Museum is lamentable to report the passing of Bob Dyson, who served as Williams Managing director of the Museum from 1982 to 1994 and took part in many important excavations associated with the Museum. He was a professor of Anthropology at the Academy of Pennsylvania for 40 years and founded the Louis J. Kolb Social club, which provides financial support to graduate students who deport research on topics related to the aboriginal world. Here, we review Bob'southward life and the contributions he made to archaeology and to the Penn Museum.

The Penn Museum is sad to report the passing of Bob Dyson, who served as Williams Director of the Museum from 1982 to 1994 and took part in many of import excavations associated with the Museum. He was a professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania for 40 years and founded the Louis J. Kolb Society, which provides financial support to graduate students who conduct research on topics related to the ancient world. Here, we review Bob's life and the contributions he made to archæology and to the Penn Museum.

ROBERT HARRIS DYSON, JR., globe-renowned Nearly Eastern archeologist, scholar, educator, and Manager Emeritus of the Penn Museum, died peacefully afterwards a long illness on February 14, 2020, in Williamsburg, Virginia. He was 92.

Dyson was born on August 2, 1927, in York, Pennsylvania, the only child of Robert and Harriet (Duck) Dyson. He was educated in the public schools of Forrest Hills, New York, and the Runnymede Collegiate Institute in Ontario, Canada. At 17 he enlisted in the U.S. Navy, serving in China.

Honorably discharged from the Navy, in 1946 he enrolled at Harvard University and graduated magna cum laude with a B.A. degree in 1950. A member of the Harvard Society of Fellows, he received his Ph.D. in Anthropology in 1966, specializing in Almost Eastern Archaeology but with a broad involvement in Asia under the tutelage of Professor Lauriston Ward. Once asked how he decided to go an archeologist, Dyson replied that as a child he loved to detect rocks and minerals and save them, and his grand- mother sent him postcards from her travels. He wanted to visit those places and find out more than.

Inflow in Philadelphia

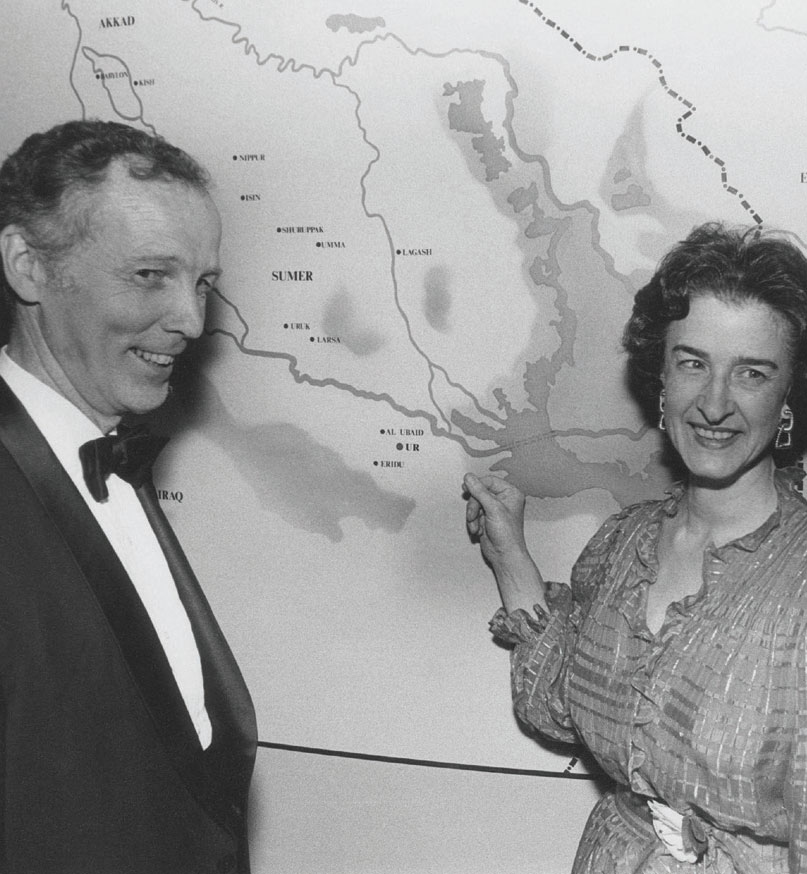

Dyson outset came to the University of Pennsylvania in 1954 as an assistant professor in the Anthropology Department and assistant curator in the Most East Section of the Museum, where he was responsible for the installation of the Mesopotamia Gallery in 1954–1955. He was tenured in 1962 and promoted to Professor of Anthropology in 1967, when he too became Head Curator of the Most East Department.

In 1979, Dyson was appointed Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Penn. He served in this capacity until 1982 when he was named the Williams Director of the Penn Museum, holding this position until his retirement in 1994.

During his years as Director, Dyson supported expeditions around the earth. He as well took on structural and internal improvements to the sprawling Museum building that had been neglected over the years. He established new ties with the University administration, reorganized the Registrar's and Business organization Offices to brand the Museum inventory more accessible to scholars, and developed a solid foundation for the Museum's finances.

In 1987, Dyson founded, with Peter Paanakker and Jerome Byrne, the Louis J. Kolb Foundation and the Louis J. Kolb Guild, which provide fellowships and financial assistance to graduate students at Penn in disciplines related to the mission of the Museum (primarily in the departments of Anthropology, Classical Studies, History of Art, Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, and Due east Asian Languages and Civilizations). Dyson served equally president of the Kolb Society until his retirement from Penn.

From left to correct, front row: Jerome C. Byrne (Secretary/Director), Renata Holod (Senior Swain), Eliot Stellar (Senior Beau)

middle row: Lada Onyshkevyech (Inferior Fellow), Bien Chiang (Junior Fellow), Matthew Adams (Junior Fellow), John Lawrence (Junior Swain), and Ruben Reina (Senior Fellow)

dorsum row: Robert Dyson (President), Bratislav Pantelic (Junior Fellow), Peter Paanakker (Treasurer/Founder), Bernard Wailes (Senior Fellow), and James Muhly (Senior Fellow).

Wide-Ranging Interests

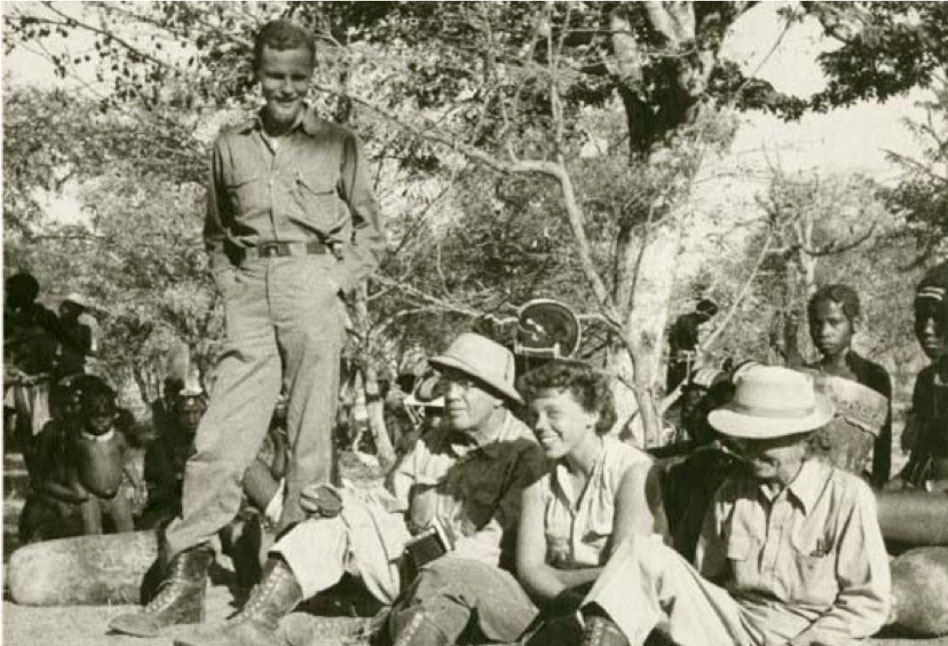

Dyson'due south training and research extended over a broad geographical area. While a graduate student at Harvard, he participated in the Point of Pines archaeological field school in Arizona, and in 1951 he represented the Peabody Museum equally anthropologist on the first Marshall Expedition to study the Kalahari Bushmen of southern Africa. (See Expedition 58.3 [2016]: 28–37 for an article by Ilisa Barbash on Dyson'due south travels in Africa.)

Dyson conducted his dissertation enquiry at the of import Iranian site of Susa, where he constructed the first stratigraphic cess of the prehistoric periods under the direction of French archaeologist Roman Ghirshman. Every bit a talented archaeologist, he participated in excavations in Iraq, Jordan, the Farsi Gulf, Pakistan, and Turkey, and, in 1962, served as manager of the Museum's Tikal Project in Guatemala.

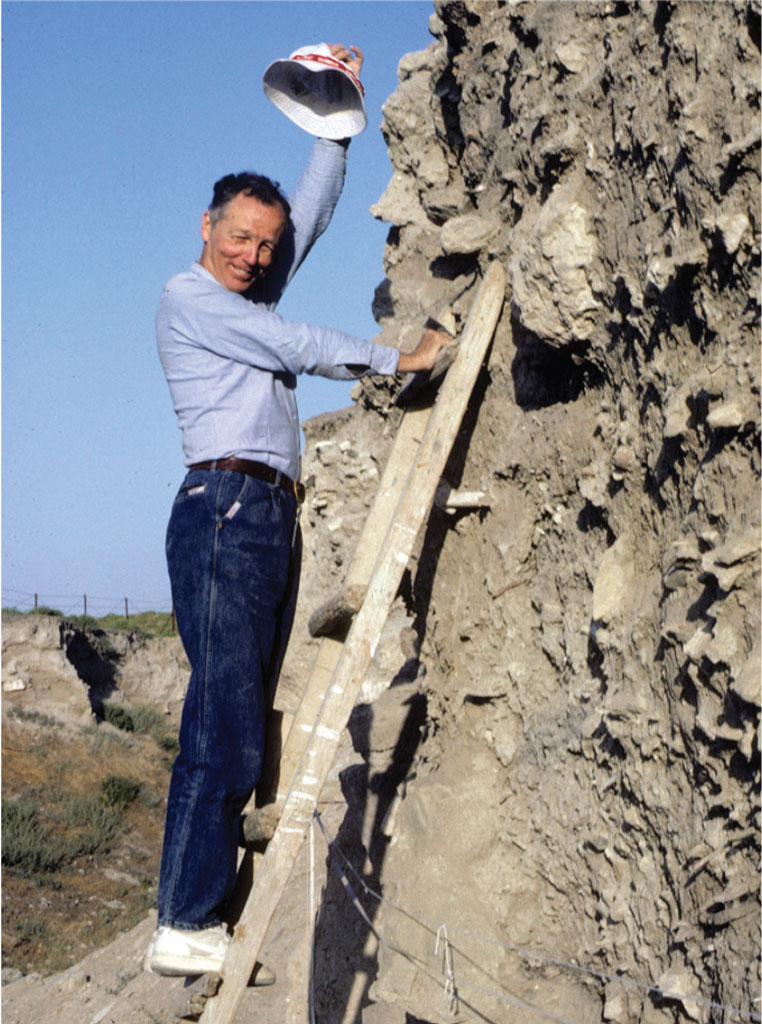

His well-nigh important contribution equally a field archeologist was every bit managing director of the Museum's excavations at Hasanlu from 1956 to 1977 ( jointly sponsored by the Iranian Archaeological Service, and for many years by the Metropolitan Museum of Art). The site of Hasanlu in northwest Iran was destroyed during the tardily ninth or early 8th century BCE by what appears to have been a sudden armed services attack, probably by an army from the kingdom of Urartu in what is now eastern Turkey. Dyson and his team excavated a serial of large buildings that had been burned, including a palace and what is probably a temple. Most of the buildings had non been emptied of their contents, preserving a range of artifacts in the places that they were used or stored.

Among the more vii,000 items formally recorded by the earthworks staff were household tools and pottery, seals, jewelry, weapons and armor, horse gear, and ivory plaques that depicted myths and palace life as well every bit warfare. More than than 200 bodies were discovered cached in the ruins of the collapsed buildings and open courtyards, including armed men, women, and children killed in battle, murdered later as captives, or trapped by the fire that destroyed the settlement.

With the discovery of the gilt bowl at Hasanlu in 1958, Dyson and the University of Pennsylvania team became famous through a multipage spread in LIFE magazine (1959). The bowl (now in the National Museum of Islamic republic of iran) is actually a large and unique gold vessel, beautifully decorated with mythological scenes—an important object for our understanding of belief systems in Iron Age Iran. It too gave scholars a rare glimpse into a moment in the past: crushed in the collapse of a mudbrick building, the bowl was found in the skeletal easily of a warrior who appears to have been fleeing the 2d story of a building as it fell.

Instructor and Mentor

Dyson was a skilled excavator and mentor. The Hasanlu Project served for two decades every bit the premier grooming ground for American and foreign archaeologists interested in pre- and proto-historic Iran. At sites such as Hasanlu, Dinkha, and Hajji Firuz, Dyson taught students how to understand the germination of archaeological deposits by examining processes in modern fields and settlements. Removing deposits during earthworks required attending to soil color and texture, but likewise an agreement of events, some very small (soil done off mud brick walls) and some very large (the plummet of two-story burned buildings). Perchance Dyson's greatest legacy will be his mentoring of multiple generations of archaeologists and art historians, both in the field and in the classroom. Many of these former students went on to illustrious careers and founded their own excavations at important sites throughout the Center Due east and Asia.

Dyson was an active member of numerous scholarly organizations, oft serving in leadership positions. He was president of the Archaeological Constitute of America from 1979 to 1981 and president of the American Constitute of Iranian Studies in 1968 and from 1987 to 1989. He was a member of the Society of Fellows at Harvard University, the American Philosophical Gild, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He received honors from the Athenaeum of Philadelphia and the Instituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, and was a Decorated chevalier de l'Ordre des Artes et des Lettres (France). He was awarded the Order Houmauyoun (4th Rank) by the Shah of Iran in 1977.

Dyson leaves no immediate family unit, having been pre-deceased by his partner of many decades, Urban Moss, merely is survived by a large synthetic family unit of friends and former students. After retirement, Bob Dyson spent his after years enjoying life in a 19th-century brick farmhouse in Essex, New York (surrounded by friends both human being and fauna); in a business firm on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C.; and in a community of seniors in Williamsburg, Virginia. A memorial program will have place at the Penn Museum when circumstances allow.

Memories

A Wonderful Teacher in the Field

Bob Dyson was highly respected as an excavator, with an incredible power to document and explain complex stratigraphic processes. And he was a wonderful teacher in the field, showing the states how to dig, how to understand what we dug, and how to run a field project. Dyson was my dissertation advisor, and I excavated with him in Iran at Dinkha Tepe, Hajji Firuz, and Hasanlu. He worked with me at Gordion, where he appointed me every bit director of digging and survey in 1988. I was his research banana at the University Museum from 1982–1991, when he appointed me editor of Expedition. We published together, and we traveled after he retired.

His Penn students take directed archaeological projects in Iran (John Alden, C.C. Lamberg- Karlovsky, Louis Levine, Shapur Malek Shamir-Zadeh, Ilene Nicholas, William Sumner, Mary Voigt, Harvey Weiss, T. Cuyler Young), Turkey (Timothy Matney, Mitchell Rothman, Elizabeth Stone, Thousand. Voigt), Armenia (Yard. Rothman), Syrian arab republic (Michael Danti, Gil Stein, H. Weiss), Iraq (Elizabeth Stone), Kurdistan (K. Stein), Islamic republic of pakistan (George Dales, Rafique Mugal), Tajikistan (C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky), the Arabian Peninsula (Chris Thornton), Bharat (Carol Kramer),and Thailand (Vince Pigott).

Encouraging a Volunteer

Bob took me to Hasanlu in 1959 as role of The Hasanlu Projection squad. This was my first archaeological excavation. I was a raw "newbie," a volunteer at age 22, taken along equally an artist. When we arrived, Bob took me up on the mound to show me stratigraphy, and then digging. He gave me his trowel and I dug into the baulk. Klunk!! I hitting an object! I was hooked.

Back at the Museum I held several positions under Bob's direction in the Near East Department, working on collections direction, helping scholars and visitors access the collection, and helping with and developing exhibitions and publications. Currently I am completing publication of the Hasanlu horse equipment, a task Bob gave me some 25 years ago.

I run across myself every bit an example of Bob's kindness, insight, intuition, and encouragement of interested people of all kinds—as well every bit the scholars. Nosotros were all students that he taught so well.

Reaching Out to New Audiences

When I wanted to showtime a airplane pilot radio series with voices from the archaeologists and other cardinal participants in major excavations, Bob helped me get funding and took the pb in the segment on Hasanlu, Iran. The result was "Buried Treasure: Newscasts from the Ancient Past" which premiered on WHYY/Philadelphia radio, aired on all the public radio stations in Pennsylvania, and was distributed to libraries throughout the state. The consummate, unedited recordings—truly historical!—are at present in the Museum Archives.

In the early 1980s I was establishing the University Museum'southward Public Information Office at the aforementioned time Bob Dyson was working to amend the Museum's internal construction and operations. He wanted to reach out to larger communities, to attract new audiences and supporters, while staying true to the unique nature of the Museum. I was part of that effort.

Often, I would inquire Bob to endeavour something "new and different"—a big paper or magazine story, an innovative radio series, a Boob tube project, a Museum community collaboration. He always said yep and was both supportive and personally involved. He understood information technology was function of his Museum leadership to be up front, so others would follow. Information technology was an exciting time!

Bob Dyson and Persian Ta'arof

Ane of the particular delights of Tehran in the early 1960s was the broad range of pocket-sized but distinctive restaurants where one could dine. In the intervals betwixt seasons, Bob and I were more than willing to pb small-scale groups of happy archaeologists to ane or another of these reputed hostelries. On i evening, the shine progress of a particular "expedition" was abruptly interrupted: although nosotros were a political party of v and had hailed a cab with five empty seats, information technology was the distribution of the final two seats that created a problem.

Bob and I were the two still-unseated members of the grouping. And each of united states of america had been, within the past few months, in the "suicide seat" beside a reckless taxi commuter in the class of something approaching a caput-on collision. Naturally, the last thing either of us wanted to do was to sit beside the present driver! Normally, we would take tossed a coin to see who was going to occupy the empty back seat, merely since we each thought we could use the conventions of ta'arof (the Persian fine art of piling 1 compliment on height of another) to our own advantage, nosotros kept on arguing most who should sit in the empty seat for the longest time. In the end, the others in the back seat literally pulled me into the cab through the open up back door, while Bob, a perfect gentleman to the concluding, graciously occupied what could also be called "the seat of honor." It was, afterward all, the merely conceivable outcome.

A Chief at Stratigraphy

Robert Dyson was my professor, mentor, and friend. He was knowledgeable and wise. We knew nosotros had to listen advisedly when he talked equally every interaction with him was a learning experience. He was always thinking about things in new ways, ever figuring things out, always soft spoken, pocket-size, and kind.

The get-go form I took with him was his survey on the archaeology of the Aboriginal Virtually Eastward. We met 1 evening a week in the refurbished cranium room in the home he shared with Urban Moss in Philadelphia'due south Club Hill. Later the lecture, nosotros ate the dinner (on our laps spread around the house) that had been prepared by Urban and Mary Virginia Harris, and discussion continued into the evening. This is i of the many ways in which Bob created personal bonds with his students, but we besides understood that nosotros had to evangelize to his standards, non disappoint him.

Equally a teacher and mentor, he was dedicated to our professional person development. The Kevorkian Lecture Series, which he founded, as well equally his reputation as a distinguished scholar brought important people in Almost Eastern archaeology to Penn. Bob always made certain that his students had an opportunity to interact with these scholars and participate in various forums with them, expanding our horizons likewise every bit our contacts.

Bob is responsible for the development of archaeologists who went on to make important contributions to the field. He was a master at stratigraphy and made sure we did not miss anything in our squares. He made life on the dig enjoyable and from time to fourth dimension, to his (and our) great delight, he surreptitiously squeezed watermelon seeds across the dinner tabular array, starting water fights. He would just laugh, his eyes tightened with a mischievous wait. Equally assistant manager at Hasanlu I learned everything from Bob I needed to know to run my own field seasons in time. Well-nigh importantly nosotros worked hard, learned a lot, just besides had fun. For me, these are the "good onetime days" I shared with nifty friends, colleagues, and the wonderful Iranians who worked with us on the site.

Bob Dyson was an outstanding thinker, scholar, and teacher, and I feel very privileged to take known him.

A World of Scholarship and Achievement

I e'er liked seeing Bob. He represented another world to me—of scholarship, of achievement, of broad and mature perspective, of sagacity. As a student of Bob'southward, he was e'er very kind to me, though I never quite got over being terrified of him. I e'er thought he was a squeamish human being, and a good i. He had a lovely smiling.

How the Kolb Foundation Began

One day, I received a call from Bob Dyson with an invitation to go out to dinner to a Center City restaurant with a special guest and a small grouping of colleagues. The guest'south name was Peter Paanakker. The dinner was tasty, the visitor interesting, the conversation lively. Still, the near electrifying news was that Peter was thinking of setting up a way to commemorate his female parent, Katherine Paanakker, by establishing a foundation that would provide fellowships to support students at Penn who were engaged in the written report of the cloth culture of pre-modern societies. The Kolb Foundation would be named in memory of Katherine's father, Colonel Louis J. Kolb, a prominent Philadelphian and 1887 graduate of Penn. The model was the Junior and Senior Fellows organisation at Harvard University.

By 1990, a substantial add-on was made to the Kolb endowment, and the terms were changed to specify that the Foundation would back up graduate study in pursuit of a Ph.D. caste. Furthermore, rather than simply a jolly annual dinner with drinks beforehand, the tenor of the events changed to a more than serious academic i, with some of the Junior Fellows presenting their piece of work at one effect, and a colloquium or seminar-type upshot organized around a topic such equally "Places of Retentivity." These events and a dinner now occur yearly and help to track the progress of the Junior Fellows likewise equally to develop larger topics of involvement for the entire fellowship.

A Trip Not Taken

I always enjoyed Bob'due south friendly presence. I well recall how he showed me around "his" galleries before long after my arrival at the Museum in the autumn of 1977. He was peculiarly proud of the finds from the trek to Ur of the Chaldees in which the University Museum had joined with the British Museum in the 1920s. Pointedly, Bob drew my attending to the decomposable state of some of the copper bowls from Ur, hidden from sight, as it were, in the drawers below the cases with the stunning artifacts. We agreed at once to go them conserved.

A later moment I especially recall was in 1979. We had planned to go out together to see his site at Hasanlu in Islamic republic of iran where he had been working with stunning results for some xx years. The airplane tickets had, I think, been purchased. At least that was the plan—until the moment when he looked round my door early the morning of eleven July: "I don't think we'd ameliorate become, the Shah has merely been deposed." We never did go on that trip. And I was not to get to Islamic republic of iran for many years and, sadly, never to Hasanlu.

I was delighted when he took over the directorship of the University Museum from me in 1982.

Part of His Very Large Family

With his very close connection to Edith Porada, the art historian, archaeologist, and authority on cylinder seals, Bob Dyson was a mentor to me from the offset of my studies at Columbia University. He listened, asked the right questions, played out various scenarios, and gave me good and sensible advice. Bob really was the Father of American Archaeology in Iran, and I felt role of his very big family.

Completing a Circle

I admired and respected Bob so much. He had an enormous influence in shaping my interests, my outlook, and the course of my life as an archaeologist. I still tell people stories well-nigh the way he taught me how to read site reports, and his extremely depression tolerance for bullshit. I was very intimidated by Bob, but over time I realized that it was because he had high standards and that he wanted his students to alive upwardly to those standards.

One of the neatest moments for me was when I was leading an Oriental Institute tour of Iran in 2016, and Jebrail Nokandeh, the managing director of the museum in Tehran, let me run across the finds in their basement "Gilded Vault." He allowed me to concord the Hasanlu gold bowl. When I held information technology in my easily, I felt such a stiff connection to Bob. I felt similar my being in that location was completing a circle that he had begun decades before.

One time I became interested in Afghanistan and Central Asia, I realized how far-sighted he was in seeing the importance of these regions for understanding the Middle East and the Iranian world. Bob was a truly smashing man, and he shaped generations of students who volition never forget him. I am proud and grateful to take been ane of those fortunate people.

The Museum as a Research Institution

Bob Dyson had a real vision of the Penn Museum. He saw it as a serious academic research institution, just also a museum with exhibits, programming, and publications similar Trek magazine that interpreted and presented its collections and inquiry to the general public. Bob supported field research with all the resources he had available, and he told me in no uncertain terms, when I commencement came to Penn in 1986–1987, "Your job is to dig for me." Bob also believed in sending members of the Museum staff into the field, so they could gain a better agreement of what archeology was all about and exist more effective and enthusiastic in promoting the Museum.

Bob started out with a deep interest in prehistory. His earliest publications were on the domestication of plants and animals. Just, his excavations at Hasanlu took him in other directions. He understood the importance of his work at Hasanlu and the surrounding region, just he likewise had some perspective and even a sense of humour virtually his work. He knew finding the gold bowl made his career, and he in one case told me, in a rare moment of candor, that if he hadn't found the Golden Bowl, he would have ended up selling socks in Wanamaker'south, once Philadelphia's premier department store. Of course, Bob also took pride in training time to come archaeologists, and the Ph.D.s he produced, also every bit those he influenced from afar, constitute a virtual "who's who" of archaeology across continents. Bob was, in many ways, a seminal figure in archaeology, and I will exist forever grateful for all the opportunities he gave me over the years.

Beyond His Ain Specialization

At the passing abroad of my great instructor, I am reminded of his course "Urbanization in the Ancient Near East," which inspired me to think of the Indus Valley and the concept of Early Harappan for my Ph.D. thesis in 1970. Since the discovery of Indus culture, this was a major change in thinking, as best-selling by international scholars. I and my colleagues in Southern asia and the earth are obliged to Bob for his significant contributions beyond the regions of his own specialization.

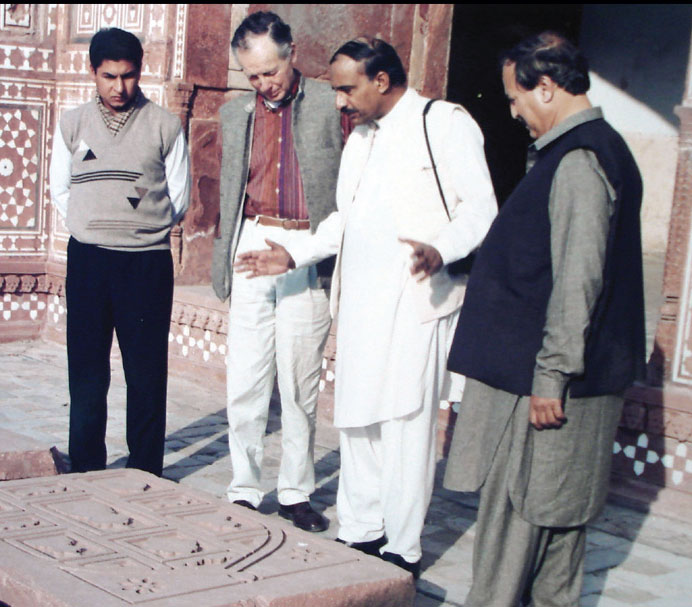

At this very pitiful moment, I recollect his visit to Pakistan, a visit I had requested for 24 years. I had the honor of taking him to various places in 1994 and presenting him with an album at Dr. Bob'southward Last Graduate Student the terminate of the visit. When I was at Penn, I was the only educatee who had the unique award of living in his old colonial firm in Philadelphia for 2 summers when he went to Islamic republic of iran with students.

Memories such as this and many more of his generous hospitality, supervision of my studies, and support even after I returned to Pakistan will remain enshrined in my heart and of my family members forever. May Almighty Allah anoint his soul. Amen.

Dr. Bob's Concluding Graduate Student

On my first solar day at Penn in 2002, the Department of Anthropology welcomed the new accomplice of graduate students by asking one of the emeritus faculty members—Robert H. Dyson, Jr.—to speak most what Penn was like when he starting time arrived. Prof. Dyson's name was equally mythical to me equally Franz Boas or Margaret Mead. I came to Penn to focus on Virtually Eastern archeology, especially Iranian and Central Asian prehistory, and Bob Dyson was the starting time American to open up that expanse for report in the 1950s.

They asked all the first-year grad students to introduce themselves, I confidently said "I'g Chris Thornton, and I focus on the archæology of Islamic republic of iran and Primal Asia." As I saturday down, I looked nervously at Prof. Dyson, expecting to see some acrimony or frustration that I had never thought to contact him earlier coming to Penn. Instead, he looked at me intently, smiled, and raised a hand in a friendly "howdy."

I worked with "Dr. Bob" my unabridged time at Penn, somewhen writing my dissertation on excavations carried out by Dyson in the 1970s. We traveled to Iranian collections in Europe and worked on two publications together. I only knew Bob Dyson in the last two decades of his life, but fifty-fifty then, he proved to exist an excellent mentor and teacher, and I'grand grateful for having known him.

The Discovery of a Lifetime

Dyson Talks to LIFE Magazine in 1959

The master sleuth of the Mannaean mystery is a 31-year-old Robert Dyson, Jr., the Pennsylvania University archaeologist who headed the dig. After three months of dawn-to-dusk spadework, his team exposed most of the metropolis's palace. Then 1 evening a pickman uncovered a man'south mitt and arm. "The finger basic were stained green from the verdigris of rows of bronze buttons under the skeleton," Dyson recalls. "The money-size disks were a form of armor, unknown to us, fabricated of buttons sewn close together on leather." With T. Cuyler Young, Jr. and Charles A. Burney, his assistants, he began brushing silt off the bones and unexpectedly revealed a bit of golden. "thinking it was a bracelet, I brushed some more. Our eyes got bigger and bigger as the sliver became a strip, and and then a sheet, and then a gilt basin. Lifting it gently from the arm bones, I stuck it inside my shirt and went over to where our secretary, Caroline Dosker, was giving the workmen their day'south pay. Pulling out the vessel, I held information technology loftier: 'Hither it is men–the discovery of a lifetime!" Every bit the aureate glowed in the sunset, the group stared in atheism. We nicknamed it Baby. Earlier taking Baby to a vault for safekeeping, we washed it and filled information technology with vino. Then we all drank a toast: 'From Mannaean lips to ours.'"

From "The Secrets of the Golden Bowl: Unknown Culture is Unearthed," LIFE magazine, Jan 12, 1959, page 60. Courtesy of LIFE and Meredith.com.

EDITOR'S Note

During the catamenia Bob Dyson served as Williams Director, the Museum was called the University Museum. Those references accept been left as written, although we are now the Penn Museum.

Thank you to Phoebe Resnick, Mary Voigt, and Christopher Thornton for writing this tribute to Dr. Robert Dyson with help from Senior Archivist Alessandro Pezzati, Maude de Schauensee, and Vince Pigott. Thanks also to Richard Zettler, who provided many photographs from Hasanlu, and to Bob's colleagues and friends who sent in additional photographs and memories.

Source: https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/remembering-bob-dyson/

0 Response to "Penn Museum of Art and Archaeology Volunteer David Biberman"

Post a Comment